We have new projects for this new stage in 1051 Magazine, and one of them is this section called Soundtrack Of Our Lives.

Here we will do electronic music archaeology, to get closer to records that have been important, some known, others not so well known, or simply records that are worth remembering.

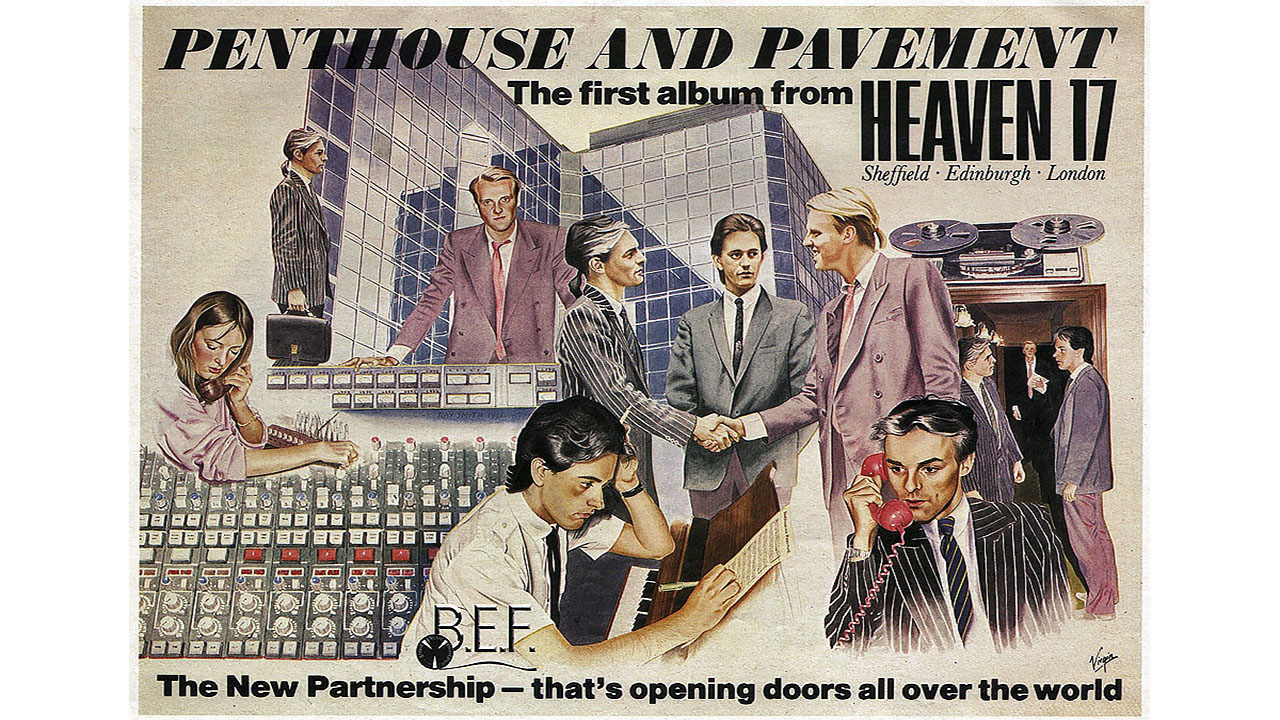

As this month marks the 40th anniversary of a true masterpiece, we’ll get down to work to talk a bit about that Penthouse & Pavement from Heaven 17.

Let’s do a bit of history, let’s put ourselves in situation. Sheffied, England, the heart of the UK’s steel industry (the city pivoted around that industry), the seventies. Maggie Thatcher began the decade as Minister of Education, but in 1974 the Conservatives lost the elections, a Labour government came in and the Iron Lady became head of the opposition party until 1979, when she won the elections and became Prime Minister of the country… with all that this entailed.

British industry was in dreadful decline, due to the unstoppable post-World War II rise of the United States and the renaissance of other industries such as Japan. All this coupled with the British idiosyncrasy that made them unwilling to change and improve their processes… but… aren’t we going to talk about a record? ? Indeed, but all this is crucial for the birth of that record. Yes, we are in other times when even a record made to dance and enjoy had a huge political and social charge in its message.

Martyn Ware, in 2010 in an interview for The Quietus defined the situation in Sheffield in those days very well:

“It was quite Sheffield. Well, the North in general is like that, but Sheffield in particular is a city of unexpected juxtapositions. Because on the one hand it’s good, honest, working class, puts a lot of effort into it and it will sound great, craftsmanship, and on the other hand, at that time, a desire to escape from mundanity because of unemployment and lack of prospects.”

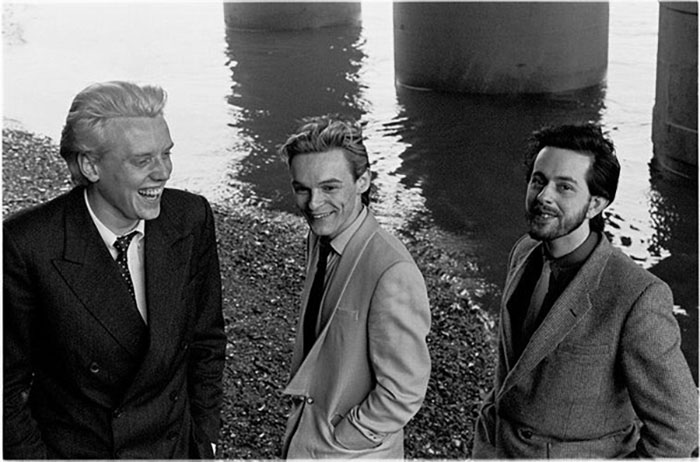

Let’s talk about its protagonists. Martyn Ware was born on 19 May 1956 in Upperthorpe, Sheffield, where he grew up in a working-class family. His father was a steel factory worker and his mother worked on the factory production line. When he left school he worked for about three years in the fledgling computer industry, and with his first wages he bought his first synthesiser, a Korg 700S, with which he began to experiment with new sounds.

Then there is Ian Craig Marsh, also born in Sheffield (11 November 1956), who also found work as a computer programmer like Martyn (though not in the same company). But first, he joined the local youth theater group, Meatwhistle. There he met Mark Civico, with whom he formed a satirical “theatre-rock” group called Musical Vomit. They took their name from a Melody Maker review of a gig by New York band Suicide, which described them as “musical vomit”.

They only played together twice, with Ian accompanying Mark’s vocals by making noise with his cheap Woolworths guitar, before Ian was expelled from his school after being labelled “an undesirable subversive element”.

Precisely in Musical Vomit, Ian meets our third protagonist, Glenn Peter Gregory, another son of a steelworker who came into the world in Sheffield on 16 May 1958. Glenn wanted to be an actor when he was young, but ended up taking up music before making a serious attempt at photography. Around 1973/4 he joined Ian in a band with the beautifully named Music of Honour, where he used to play bass and later became a singer with Musical Vomit. He later coincides with Martyn Ware in a couple of bands, VDK and Stud.

Let us now turn to the background closer to the birth of Heaven 17, where the paths of these three friends cross. In 1977, both Ian and Martyn were working as computer operators (for tool manufacturer Spear & Jackson and car parts distributor Lucas Service respectively). Martyn: “I had just started working in a well-paid job and, for the first time in my life, I had some money to spare… what was I going to spend it on? What was I going to spend it on? The first – cheap – commercial synthesizers had just come on the market, so I went out and bought one”.

In June 1977, Adi Newton, Martyn Ware and Ian Craig Marsh, formed a group called The Dead Daughters, to perform at a private party held at Sheffield University bar for a one-off gig. Their next incarnation was the legendary and mythological Studs, who played a chaotic and anarchic gig. The band consisted of Adi Newton (Clock DVA), Martyn Ware, Ian Craig Marsh and Glen Gregory, Richard H. Kirk, Stephen Mallinder and Christopher Watson (Cabaret Voltaire), and Hayden Boyes (2.3). Following this, Ian, Martyn and (briefly) Adi Newton form The Future, while Glenn was briefly in a band called 57 Men before moving to London to start a career as a music photographer.

The Future evolve into The Human League when Adi leaves to form Clock DVA and Martyn and Ian find themselves in need of a new vocalist. They talk to Glenn, but he is in London focusing on his career as a photographer and they bring in Philip Oakey, who was working as a porter in a hospital at the time. Although he had no previous musical experience, he was known on Sheffield’s underground circuit for his quirky stylings. Soon after, Philip Adrian Wright joined the band to take over the visual side of the group.

Two singles on Fast Product, the label of Bob Last, who became their manager, led to a signing with Virgin and the release of two albums in 1979 and 1980, Reproduction and Travelogue. These first two albums are dense, although Travelogue shows a slight commercial shift, as sales did not match the good reviews. Martyn and Philip constantly clashed, as their visions on the line to be followed by the band were far apart. Martyn Ware says that one day he arrived at the studio, where Bob Last and Philip Oakey were, and they told him that they were going to kick him out of the band… “but the band is mine, how could they kick me out”. They did, and Oakey insisted on keeping the name of the band, at a cost to his pocket.

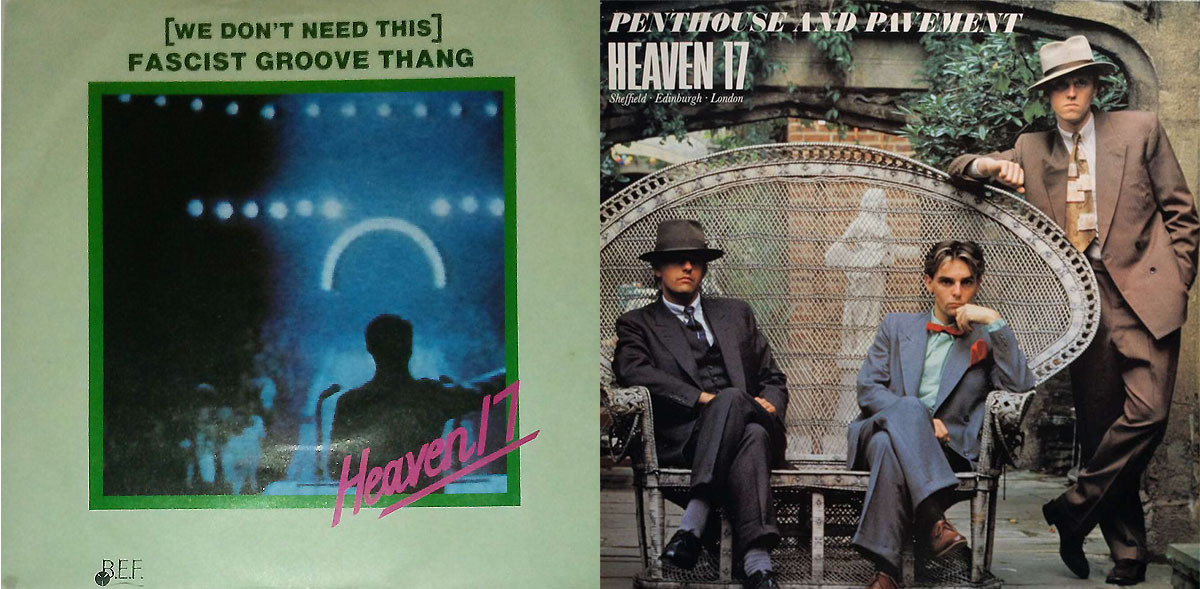

Bob Last tries to persuade Martyn to form a “production company”, and so the British Electric Foundation (B.E.F.) is born, but at the same time, Martyn talks to Glenn Gregory (who was in Sheffield taking pictures of Joe Jackson) and invites him to be the singer of Heaven 17 (a name taken from a fictional pop band mentioned in Anthony Burgess’s novel A Clockwork Orange). He accepts and the band is formed, and in those early days, it was all madness, with the trio working on Penthouse & Pavement and Music Of Quality & Distinction Vol. I, the BEF’s first album, at the same time. Glenn says that they were recording (We Don’t Need This) Fascist Groove Thang at the same time as Anyone Who Had A Heart. Things like that are only within the reach of the greats geniuses…

Bowie said of the first incarnation of The Human League that they were “the future of pop music”. Heaven 17’s first album was to be something that had not been heard before.

In the words of Martyn Ware, “The idea that we could incorporate what was in our soul, which at the time was a political consciousness. For example, we were fans of Gil Scott Heron. We were very influenced by the black groups in America at the time. Curtis Mayfield, Parliament, Funkadelic, social activists. We had a certain empathy with what they were singing… Chocolate City and that. It was almost like we were the blacks of Sheffield… [laughs] It sounds ridiculous now! But that’s the way we thought.”

Ware was also heavily influenced by the sound of Sheffield: he likens the noise of the steelworks forges to “the heartbeat of the city”. “The place where we rehearsed was an old homeware shop. Fundamentally, I was constantly surrounded by the sounds of industry, which seemed completely normal to me”.

We already have an unbeatable mix that hasn’t been used before. Add to this the synthesizer and computer savvy of Ware and Marsh, along with the unmistakable voice of Glenn Gregory and a few additional additions, such as a young bass player from Sheffield called John Wilson, who turned out to be a master on rhythm guitar (so important in Penthouse & Pavement) and the use of the Linn Drum in its first version.

The album was released in September 1981, and on the A-side of the record, called Pavement, there was a real anthem called (We Don’t Need This) Fascist Groove Thang, which has been talked about so much. Both for its almost 157 BPM and for its clear and clear message that earned them a ban by the BBC (which, as almost always in these cases, gives a tremendous media boost, just ask the Pistols, for example). Unfortunately, it was a prophecy of something that, forty years later, is still being repeated:

“Have you heard it on the news?

About this fascist groove thang?

Evil men with racist views

Spreading all across the land”

The track was released as the first advance single from the album in March 1981.

Then came Penthouse & Pavement, electronic funk that received vocal support from Californian Josie James, a black vocalist who did an excellent job on this track. A message with allusions to the slavery generated by savage capitalism wrapped up in a perfect danceable artefact, which was released as the third single in November 1981. The third track was Play To Win, which hit the shops in August 1981 as a warm-up for the album’s release. Another straight shot to the dancefloor with more of a social message. Closing that first part of the album was Soul Warfare, an ode to selling your soul to the crusty capitalism that was beginning to destroy the UK at the hands of Mrs. Thatcher.

The B-side was called Penthouse, which opens with different sounds that arrive in Geisha Boys And Temple Girls, a nuanced relationship tale. Then comes one of the best tracks on the album, with a message that was misinterpreted by many. Martyn Ware later clarified that Let’s All Make A Bomb was written with a new nuclear language in mind, inspired by that hope called the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

“Take one hundred scientists or more

Place in a room and lock the door

Let them confer for half their lives

Unlock the door, go in and see

What they have made for you and me

A brand new toy to idolize”

Let’s All Make A Bomb is another of the hidden gems of this album, which combines in such an unprecedented and perfect way that Sheffield industrial influence mentioned more than once by its authors with passages that could be perfectly integrated in a Brazilian batucada. Once again, a forceful message wrapped in an incredible sonic landscape.

And then what was the third and last single of the album, The Height of the Fighting, another track that puts its focus on a clear and clear anti-militarist message, with more blows to capitalism included. Musically, another artifact made for dancing without concessions. The album closes with two more tracks. The first one is Song With No Name, a track that reminds us of the sound used by Martyn and Ian in those first two albums of The Human League previously mentioned, denser and deeper. To close the album they created We’re Going To Live For A Very Long Time, industrial sounds with an ironic message and a final looped repetition to put the finishing touch to a fundamental album in the history of music.

Nobody had explored those sonic horizons before them, nobody had experimented with that fusion of styles that this trio from Sheffield worked with. And if we talk about their content, about the message they spread on that first Heaven 17 album, with the passage of time two fundamental aspects can be verified. The first is that they got it absolutely right, and that became clear as the decade went by, and the second is that, 40 years later, and unfortunately, a good part of it is still valid today.